Update (18jun18): Just found an interesting reference, mentioning several insurgent groups allegedly fighting in the Al-Qaim area in early 2005. This from a “resistance” propaganda blog, and the whole piece is clearly very biased and inaccurate. Much of it is just outright lies, but in one part several groups are mentioned. Some are known (Ansar Al-Sunna, 1920s Brigades) but I’ve never heard of most of them:

Tuesday April 12: All involved Resistance groups (Jaish Ansar Al-Sinna, Mohammed’s First Army, Qaida Jihad in Raqfidain, Legions of the twenties Revolution, Legions of Al-Nasir Salah Al-Din, Abu Bakir Salafi Legions, Rahman Salafi Legions, and the Islamic Anger Legions) issued a joint statement giving the Americans 12 hours to withdraw from the perimeter of Al-Qaim to allow food and water to flow in to the civilians. Otherwise, a spike in attacks throughout Iraq will follow. In a seperate statement, an unknown group, calling itself Legions for Unifying Iraq has threatend to attack many targets, including churches, in response for prominently manifesting the Cross on American tanks.

(See the article here)

Update: Just finished a draft chapter on “The Enemy”. Download it here

(See part 1 for a meandering attempt at an intro to this key question…)

As in any insurgency, the most frustrating aspect of the war in Iraq was always figuring out who the enemy was. Right from the start, Saddam’s fedayeen fought the coalition in civilian garb and vehicles, and Iraqi soldiers and commanders quickly shed their uniforms but kept their weapons. But there was also seriously muddled thinking at the top echelons of government and military command about how to characterize the enemy. Early in the war, the Bush administration consistently used the terms ‘dead-enders’ or ‘former regime elements’ to describe the enemy. All during 2003 and 2004, openly acknowledging an insurgency essentially meant admitting that Iraq would be a long and costly war, which was a political liability. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld famously and stubbornly refused to say there was an insurgency in Iraq until mid-2005 when the semantic charade became too painful.

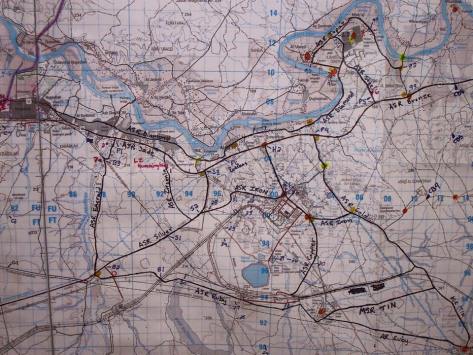

This obfuscation trickled down through the military chain of command and into the field. As 2004 turned into 2005, commanders, military intelligence officers, and public affairs spokesmen typically referred to the enemy simply as ‘anti-iraqi-forces’ (AIF), which crudely lumped together the various strains of the insurgency into a convenient, but conceptually erroneous acronym.

For anyone deployed to Iraq in 2005, however, two things were crystal clear. First, whatever approved ‘acronym-of-the-month’ was being used to describe them, there were definitely lots of armed insurgents. Second, the insurgents were anything but monolithic. There were many groups and fluidly-organized elements that were fighting against Coalition troops, with a variety of motivations. As many analysts have noted, the insurgency was never an organized, unified hierarchy but was a viral, highly adaptable and decentralized network.

One common way that the Coalition tried to build a slightly more granular understanding of the enemy was to subdivide the ‘Anti-Iraqi-Forces’ label into major sub-categories. In some headquarters, particularly among the Marines in Anbar and including RCT2 in early 2005, the insurgency was conceptually divided into three parts: criminal gangs, former regime elements (FRE) and foreign fighters (FF). But in reality, these labels were still too simplistic and misleading to be of much use in understanding the enemy or formulating an effective counter-insurgency plan.

The terms ‘criminal gangs’ or ‘criminal elements’ were very loose catchalls, which encompassed traditional cross-border smugglers, corrupt police or border guards, IED emplacement cells and guns-for-hire which offered services to the highest bidder, as well as tribal ‘security’ groups or militias. While the Marines in 2005 (and the coalition overall) were still grappling with the question of how to relate to the tribes of western Anbar, most tribal forces were simply tagged as criminals.

‘Former regime elements’ was probably the most meaningless of the labels, since Saddam’s regime had been so pervasive and intrusive that almost every male of substance in Anbar had some level of connection to the Ba’ath party apparatus, various government-controlled enterprises, the omnipresent security services or the military. Bundling an individual or group into the ‘FRE’ category was usually a shorthand way for analysts to portray them as less-religiously motivated, and less affiliated with Al-Qaida and the transnational jihadist movement. Plus, for field-grade and general officers in particular, using the term avoided the potentially loaded word ‘insurgents’ and possible heat from superiors. Thus, many figures and factions in the insurgency in Anbar were initially thought of as former cronies of Saddam, when the reality was far more nuanced. For decades, Anbaris had pushed back against government control from Baghdad, sometimes violently. Saddam had seen the fractious sheikhs and tribal leaders in Anbar not as his cronies, but as rivals that needed to be neutralized or co-opted.

The term ‘foreign fighters’ or ‘foreign fighter network’ was the most useful of the three labels, but still managed to dodge precisely defining the enemy. While non-Iraqi fighters did sometimes end up with other groups, the vast majority were recruited, transported and deployed (often as suicide bombers) by the network led by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the Jordanian jihadist who became the most wanted man in Iraq. Essentially, when the Marines of RCT2 and the 3rd Battalion referred to ‘foreign fighters’ they were talking about the group that came to be known as ‘Al-Qaida in Iraq’ or usually just ‘AQI’. And by spring of 2005, the main enemy in the 3/2’s battlespace was AQI.

However, the key point to understand about the insurgency in Iraq was its highly interwoven, amorphous character. Most of the fighters in western Anbar who were laying IEDs, sniping at troops or firing mortars at a coalition base, could on any given day fit at least two of the above labels and possibly all three. For example; the same fighter or small cell might be simultaneously associated with a so-called ‘nationalist’ insurgent group, and part of their tribe’s militia which was deeply involved in smuggling or other black-market activities. That would put them in both the ‘criminal gangs’ and the FRE categories. Additionally, if the smuggling involved bringing jihadists across the border from Syria, they could be labeled as part of the ‘foreign fighter network’.

To further complicate things, shifting loyalties from one group to another was common, and insurgent groups often splintered, taking on different names, or recombining under some new name. Moreover, certain insurgent cells were blatantly mercenary, treating violence as an opportunity for income. Usually, these would be highly proficient in some particular area, such as bomb-making or firing mortars or rockets.

In short, attempts to conceptually divide Iraq’s insurgency into discrete, neatly-packaged categories or groups was always too simplistic. Later in the war, the US military developed the expertise and methodologies to understand and portray the insurgency in more detail, which helped immensely in 2006 and 2007 as the coalition began to wage a successful counterinsurgency campaign.

But in the spring and summer of 2005, leaders and intelligence personnel in 3/2 were still trying to answer the essential questions; Who is the enemy? Where are they? How do we defeat them?

While AQI was the most prevalent enemy in the Al-Qaim district, there were identifiable non-jihadist insurgent groups in AO Denver that operated under their own banner, and would issue communiques or threats and claim credit for attacks. At times they might cooperate with each other, but remained separate entities in that time period. Almost all their members were Arab Sunnis, as was the populace of western Anbar:

The ‘1920s Revolutionary Brigades’ most easily fit the characterization of an ‘Iraqi nationalist’ group, and many of its members were former military personnel. The name referred to the 1920 Iraqi uprising against the British colonial occupation, and the group formed soon after the US-led invasion in 2003. Their rhetoric was anti-colonial, anti-occupation, anti-coalition, their stated purpose to rid Iraq of all foreign troops (including Iranian-controlled militias), and revert to an Arab, Sunni-dominated country. The main distinction between the 1920s Brigades and most other groups in Anbar was the lack of emphasis on jihad and establishing an Islamic ‘caliphate’. This translated into their tactics and how they fought. Fighters in the 1920s Brigades were far more likely to take on US troops using direct fire and IEDs, and much less likely to use suicide bombings. In general, they avoided hurting Iraqi civilians and in some instances exhibited a rough-hewn ‘code of conduct’ on the battlefield, such as not beheading captives or defiling bodies. Their main operating areas in western Anbar, however, were mostly north of the Euphrates, between Rawah and Hit, which was further east and outside of 3/2’s battlespace in the Al-Qaim district.

The ‘1920s Revolutionary Brigades’ most easily fit the characterization of an ‘Iraqi nationalist’ group, and many of its members were former military personnel. The name referred to the 1920 Iraqi uprising against the British colonial occupation, and the group formed soon after the US-led invasion in 2003. Their rhetoric was anti-colonial, anti-occupation, anti-coalition, their stated purpose to rid Iraq of all foreign troops (including Iranian-controlled militias), and revert to an Arab, Sunni-dominated country. The main distinction between the 1920s Brigades and most other groups in Anbar was the lack of emphasis on jihad and establishing an Islamic ‘caliphate’. This translated into their tactics and how they fought. Fighters in the 1920s Brigades were far more likely to take on US troops using direct fire and IEDs, and much less likely to use suicide bombings. In general, they avoided hurting Iraqi civilians and in some instances exhibited a rough-hewn ‘code of conduct’ on the battlefield, such as not beheading captives or defiling bodies. Their main operating areas in western Anbar, however, were mostly north of the Euphrates, between Rawah and Hit, which was further east and outside of 3/2’s battlespace in the Al-Qaim district.  The Islamic Army in Iraq (IAI), or Jaysh al-Islami (JAI) was another Iraqi nationalist-oriented group that sprang up soon after 2003. With some estimates crediting IAI with 10,000 members, it was probably the largest Sunni insurgent group in the early part of the war. Like the 1920s Brigades, IAI aimed at ejecting all foreign forces from Iraq and counted many former military in its ranks. But as its name implies, IAI’s agenda was more Islamist in nature and up through 2005 cooperated closely with Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) and its predecessor groups. Sheikh Ahmed al-Dabash, one of IAI’s founders, claimed to be “like a brother” to Zarqawi. By 2006, however, IAI was denouncing Zarqawi’s bloody attacks on fellow Iraqis and began openly fighting against AQI. In Anbar, IAI mainly operated in and around Fallujah and Ramadi, although some of the tribal fighters that 3/2 encountered further west may have been affiliated with IAI.

The Islamic Army in Iraq (IAI), or Jaysh al-Islami (JAI) was another Iraqi nationalist-oriented group that sprang up soon after 2003. With some estimates crediting IAI with 10,000 members, it was probably the largest Sunni insurgent group in the early part of the war. Like the 1920s Brigades, IAI aimed at ejecting all foreign forces from Iraq and counted many former military in its ranks. But as its name implies, IAI’s agenda was more Islamist in nature and up through 2005 cooperated closely with Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) and its predecessor groups. Sheikh Ahmed al-Dabash, one of IAI’s founders, claimed to be “like a brother” to Zarqawi. By 2006, however, IAI was denouncing Zarqawi’s bloody attacks on fellow Iraqis and began openly fighting against AQI. In Anbar, IAI mainly operated in and around Fallujah and Ramadi, although some of the tribal fighters that 3/2 encountered further west may have been affiliated with IAI.

Various tribal groups (an admittedly imprecise term) also fought against 3/2 and other coalition forces in far western Anbar. These could be very localized, operating only in a particular village or district, under direction of a minor sheikh. In 2003 and 2004, most of these groups and cells were fighting against US troops, first against the Army’s 3rd Cav and then the Marines, and saw Zarqawi and his foreign fighters as allies against the occupiers. In fact, distinguishing between foreign fighters and local insurgents could be difficult. Clearly, 3/2 Marines were often fighting both foreign and local fighters in the same engagement. By 2005, however, some of these tribal forces were rebelling against AQI. The most notable of these groups was the “Hamza Brigade”, an armed militia formed by the Albu Mahal tribe in and around Husaybah.

Various tribal groups (an admittedly imprecise term) also fought against 3/2 and other coalition forces in far western Anbar. These could be very localized, operating only in a particular village or district, under direction of a minor sheikh. In 2003 and 2004, most of these groups and cells were fighting against US troops, first against the Army’s 3rd Cav and then the Marines, and saw Zarqawi and his foreign fighters as allies against the occupiers. In fact, distinguishing between foreign fighters and local insurgents could be difficult. Clearly, 3/2 Marines were often fighting both foreign and local fighters in the same engagement. By 2005, however, some of these tribal forces were rebelling against AQI. The most notable of these groups was the “Hamza Brigade”, an armed militia formed by the Albu Mahal tribe in and around Husaybah.

At first I just posted the standard 2017 Birthday Message (below), but I like this one better. Not sure what unit it came from, but it shows Marines at a checkpoint in Iraq, probably around 2006 or so. The bored grunt says “Let the insurgents know that Sierra Deuce is on Bugs and we’ll be here for an hour. We wanna play. Tell em to quit being pussies and cowards, and come out and shoot at us”… Classic!

At first I just posted the standard 2017 Birthday Message (below), but I like this one better. Not sure what unit it came from, but it shows Marines at a checkpoint in Iraq, probably around 2006 or so. The bored grunt says “Let the insurgents know that Sierra Deuce is on Bugs and we’ll be here for an hour. We wanna play. Tell em to quit being pussies and cowards, and come out and shoot at us”… Classic!

The ‘1920s Revolutionary Brigades’ most easily fit the characterization of an ‘Iraqi nationalist’ group, and many of its members were former military personnel. The name referred to the 1920 Iraqi uprising against the British colonial occupation, and the group formed soon after the US-led invasion in 2003. Their rhetoric was anti-colonial, anti-occupation, anti-coalition, their stated purpose to rid Iraq of all foreign troops (including Iranian-controlled militias), and revert to an Arab, Sunni-dominated country. The main distinction between the 1920s Brigades and most other groups in Anbar was the lack of emphasis on jihad and establishing an Islamic ‘caliphate’. This translated into their tactics and how they fought. Fighters in the 1920s Brigades were far more likely to take on US troops using direct fire and IEDs, and much less likely to use suicide bombings. In general, they avoided hurting Iraqi civilians and in some instances exhibited a rough-hewn ‘code of conduct’ on the battlefield, such as not beheading captives or defiling bodies. Their main operating areas in western Anbar, however, were mostly north of the Euphrates, between Rawah and Hit, which was further east and outside of 3/2’s battlespace in the Al-Qaim district.

The ‘1920s Revolutionary Brigades’ most easily fit the characterization of an ‘Iraqi nationalist’ group, and many of its members were former military personnel. The name referred to the 1920 Iraqi uprising against the British colonial occupation, and the group formed soon after the US-led invasion in 2003. Their rhetoric was anti-colonial, anti-occupation, anti-coalition, their stated purpose to rid Iraq of all foreign troops (including Iranian-controlled militias), and revert to an Arab, Sunni-dominated country. The main distinction between the 1920s Brigades and most other groups in Anbar was the lack of emphasis on jihad and establishing an Islamic ‘caliphate’. This translated into their tactics and how they fought. Fighters in the 1920s Brigades were far more likely to take on US troops using direct fire and IEDs, and much less likely to use suicide bombings. In general, they avoided hurting Iraqi civilians and in some instances exhibited a rough-hewn ‘code of conduct’ on the battlefield, such as not beheading captives or defiling bodies. Their main operating areas in western Anbar, however, were mostly north of the Euphrates, between Rawah and Hit, which was further east and outside of 3/2’s battlespace in the Al-Qaim district. The Islamic Army in Iraq (IAI), or Jaysh al-Islami (JAI) was another Iraqi nationalist-oriented group that sprang up soon after 2003. With some estimates crediting IAI with 10,000 members, it was probably the largest Sunni insurgent group in the early part of the war. Like the 1920s Brigades, IAI aimed at ejecting all foreign forces from Iraq and counted many former military in its ranks. But as its name implies, IAI’s agenda was more Islamist in nature and up through 2005 cooperated closely with Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) and its predecessor groups. Sheikh Ahmed al-Dabash, one of IAI’s founders, claimed to be “like a brother” to Zarqawi. By 2006, however, IAI was denouncing Zarqawi’s bloody attacks on fellow Iraqis and began openly fighting against AQI. In Anbar, IAI mainly operated in and around Fallujah and Ramadi, although some of the tribal fighters that 3/2 encountered further west may have been affiliated with IAI.

The Islamic Army in Iraq (IAI), or Jaysh al-Islami (JAI) was another Iraqi nationalist-oriented group that sprang up soon after 2003. With some estimates crediting IAI with 10,000 members, it was probably the largest Sunni insurgent group in the early part of the war. Like the 1920s Brigades, IAI aimed at ejecting all foreign forces from Iraq and counted many former military in its ranks. But as its name implies, IAI’s agenda was more Islamist in nature and up through 2005 cooperated closely with Al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI) and its predecessor groups. Sheikh Ahmed al-Dabash, one of IAI’s founders, claimed to be “like a brother” to Zarqawi. By 2006, however, IAI was denouncing Zarqawi’s bloody attacks on fellow Iraqis and began openly fighting against AQI. In Anbar, IAI mainly operated in and around Fallujah and Ramadi, although some of the tribal fighters that 3/2 encountered further west may have been affiliated with IAI. Various tribal groups (an admittedly imprecise term) also fought against 3/2 and other coalition forces in far western Anbar. These could be very localized, operating only in a particular village or district, under direction of a minor sheikh. In 2003 and 2004, most of these groups and cells were fighting against US troops, first against the Army’s 3rd Cav and then the Marines, and saw Zarqawi and his foreign fighters as allies against the occupiers. In fact, distinguishing between foreign fighters and local insurgents could be difficult. Clearly, 3/2 Marines were often fighting both foreign and local fighters in the same engagement. By 2005, however, some of these tribal forces were rebelling against AQI. The most notable of these groups was the “Hamza Brigade”, an armed militia formed by the Albu Mahal tribe in and around Husaybah.

Various tribal groups (an admittedly imprecise term) also fought against 3/2 and other coalition forces in far western Anbar. These could be very localized, operating only in a particular village or district, under direction of a minor sheikh. In 2003 and 2004, most of these groups and cells were fighting against US troops, first against the Army’s 3rd Cav and then the Marines, and saw Zarqawi and his foreign fighters as allies against the occupiers. In fact, distinguishing between foreign fighters and local insurgents could be difficult. Clearly, 3/2 Marines were often fighting both foreign and local fighters in the same engagement. By 2005, however, some of these tribal forces were rebelling against AQI. The most notable of these groups was the “Hamza Brigade”, an armed militia formed by the Albu Mahal tribe in and around Husaybah.

One of the big critiques coming from the press and think-tank crowd (then and now), was that the Bush Administration, Rumsfeld’s Defense Department and the U.S. military writ large didn’t have enough subtlety to understand who we were fighting in Iraq. And that’s true in absolute terms. In 2003, American politicos, the generals, the combat troops and the intelligence agencies, didn’t understand the nature of the “enemy” in Iraq.

One of the big critiques coming from the press and think-tank crowd (then and now), was that the Bush Administration, Rumsfeld’s Defense Department and the U.S. military writ large didn’t have enough subtlety to understand who we were fighting in Iraq. And that’s true in absolute terms. In 2003, American politicos, the generals, the combat troops and the intelligence agencies, didn’t understand the nature of the “enemy” in Iraq.

Last month I made contact with Chris Ieva, who was the Commander of Kilo Co. That initiated a great email exchange, which I’m including below (with his permission).

Last month I made contact with Chris Ieva, who was the Commander of Kilo Co. That initiated a great email exchange, which I’m including below (with his permission).

Should have put this up awhile back, but got behind… I made contact w Noah Cass a couple weeks ago. In 2005 he was a gunner in WarPig (Weapons Company). Now he’s made an independent film,

Should have put this up awhile back, but got behind… I made contact w Noah Cass a couple weeks ago. In 2005 he was a gunner in WarPig (Weapons Company). Now he’s made an independent film,